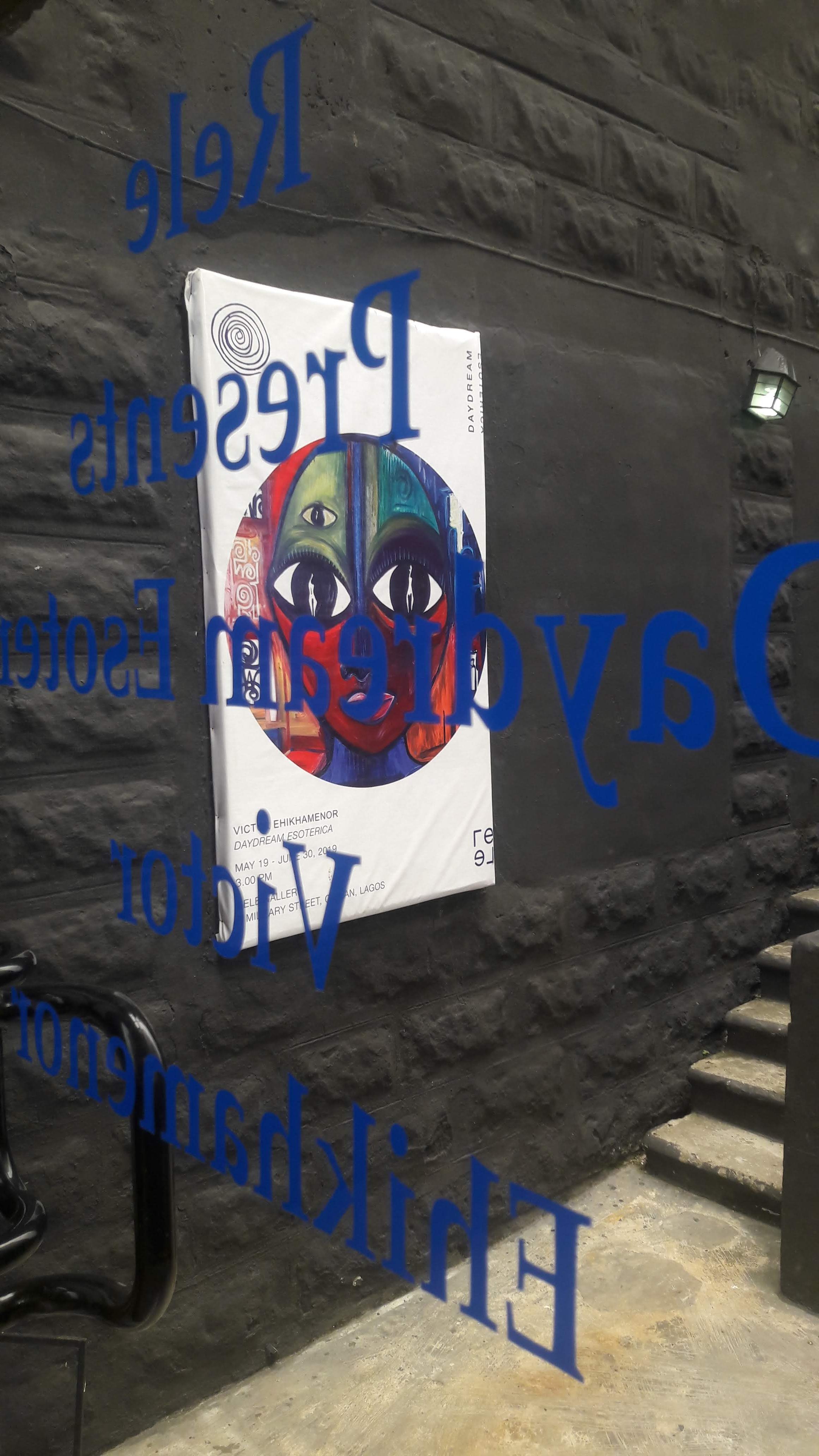

I recently visited the solo exhibition of my friend, Victor Ehikhamenor, one of Nigeria’s finest visual artists. The exhibition “Daydream Esoterica’ was Victor’s first in Lagos after an eight-year hiatus. For the art community in Lagos, this was a very anticipated event. You could tell by the buzz around the show on and offline that it was as if Lagos had been waiting for something new to happen. Plus, we were all ready for the free booze the vernissage always offers.

I wish I could say I went to the gallery with an open mind, but nope! I was already super pumped by all the buzz the event gathered. It’s like when you see the preview to a movie, and you eventually see the movie, you look out for the parts shown and see how it all fits into the puzzle. Based on the ‘pieces of the puzzle’ I had seen in the shiny lights of a PR campaign, it would be hard not to have larger-than-life expectations. Still, I tried my best to view the works within the context of the gallery, but all my anticipation building up to the viewing took over and gave me visual cues which I believe influenced my understanding of the works displayed. This is one of the effects of being an avid art enthusiast as a result of an art history background (I minored in Art History during my undergrad), I am stuck with an idealistic notion of what art is and how it should be appreciated. I must confess that this is a frustrating way to live, especially in a country that does not give art the prominence it deserves.

When I visit a gallery/museum and look at an art image or object, most times I feel I do not see what I am supposed to see. For instance, certain works of art have been put on a pedestal and glorified, but when I look at them, I usually find myself trying to figure out how or why this came to be. I am not implying that Victor’s work was being ‘glorified’, rather, that the extra buzz of the event, especially on social media, may have interrupted my unbiased perception of his work.

An actual example of placing works on a pedestal would be the Mona Lisa by Leonardo Da Vinci, one of the most famous paintings in the world which is currently housed at the Louvre in Paris, the world’s largest art museum. For a long time, I tried to understand what made this painting as prominent as it became.

My first impression of the Mona Lisa was a haunting painting of a plump, bland, Caucasian young lady with a landscape in the background. Upon closer study and more research, trying to understand the artists logic when he put the painting together, as well as the artistic movement of the time, my perception has since changed. First of all, Mona Lisa was one of the first portraits to depict a person sitting before an imaginary landscape. When Leonardo put the piece together the form of the painting has been said to be a modification of the seated Madonna, for the non-art buffs, this was a popular style back in the day and can be seen in the 15th and 16th-century portraits by artists of that era.

Wait. I’m sure by now you are rolling your eyes and wondering what Mona Lisa has to do with anything in life? Well as a Nigerian in these political times trying to navigate the needless chaos of living in Lagos, I find art to be a remarkable instrument of social change.

For one, art is just as relevant as language. It acts as a form or tool for self-expression. You find people who wanted to address social ills, societal damage, personal demons and struggles, or even the beauty they experience, and art was often the tool for their liberation.

As observers, art also enables us to engage in conversations we otherwise would not be vocal about. Imagine asking students to express their perception of an authority figure through painting or sculpture. And imagine a fundamentalist with an opposing view having to engage with that work of art and entering into the conversation it attracts. The possibilities are endless.

As a person who is more visually inclined, art reminds me of the many failings of traditional language, and how we can pick up other forms of self-expression for critical engagement at work and in society.

Maybe I’m blabbing, maybe I’m not. But after reading this, I can almost guarantee that you’d never see a work of art the same way again!